‘It’s Normal to Let Those Tears Out’: Team Lavender Helps Healthcare Workers Face Trauma

Debra Orton spends most of her time fighting a problem you probably haven’t heard of.

According to research she shared, suicide is the only cause of death that is higher in physicians than non-physicians.

There’s also more barriers that stand in the way of healthcare professionals getting help.

The same study found not only do doctors face similar concerns about stigma as the general population, but they have the added burdens of confidentiality, and fear of discrimination in licensing and hospital privileges.

This research dates back to before COVID-19.

Meet Debra Orton

Debra is a hospital chaplain by trade, but now, is highly engaged in leading Team Lavender.

It’s a project she started, hoping to tackle the problem of depression and suicides among doctors and other healthcare workers. She says a lot of the issues she encounters come from trauma that happened on the job.

When people who work in Nova Scotia’s Valley Regional Hospital are feeling the effects of that trauma, they come and see Debra.

“When people come in, I give them the opportunity to let some of those tears out,” she says. “To embrace them, in their wholeness, and to reassure them that it's normal to let those tears out.”

She is a really attentive and nice person. When we set up a Zoom interview for this story, I got a notification 15 minutes early saying she had shown up. When we started talking, she asked so many questions about me, I almost forgot who was interviewing who.

Debra made it clear her program is not a substitute for clinical methods like psychiatry – and she will often forward her visitors to those services, depending on what is appropriate. In her words, she says Team Lavender isn’t a therapy group, per se, but has therapeutic value.

That being said, she has quite a qualified roster on her team.

“We’re made up of a variety of healthcare workers, including nurses, doctors, and therapists,” she says. “We have managers on our team, administrative assistants, and so on.”

The way it works: healthcare staff, after experiencing a traumatic event, come in for de-briefs. These can be individual or group sessions. It offers a chance to get closure or express some of the things those professionals might be feeling, after experiencing what few other jobs put you through.

Debra also emphasizes that the patient comes first.

“We want to make sure that our patients and their families are always getting the best possible care,” says Debra. “Therefore, we need to make sure our healthcare workers are as well.”

She says once the hospital’s duty to patients is complete, then they turn to staff, if they’ve experienced any sort of traumatic event, and support them psychologically, emotionally, and spiritually.

Looking Out

Debra says healthcare is one of the most stressful workplaces. On top of that, Canadian healthcare workers rate their stress levels as being “high” most of the time they’re on the clock.

She adds that this stress leads to high levels of burnout. This causes some to think about leaving their job, or profession entirely. Many actually go through with it.

Debra says she knows her team can’t solve this phenomenon in its entirety – but she’s doing all she can.

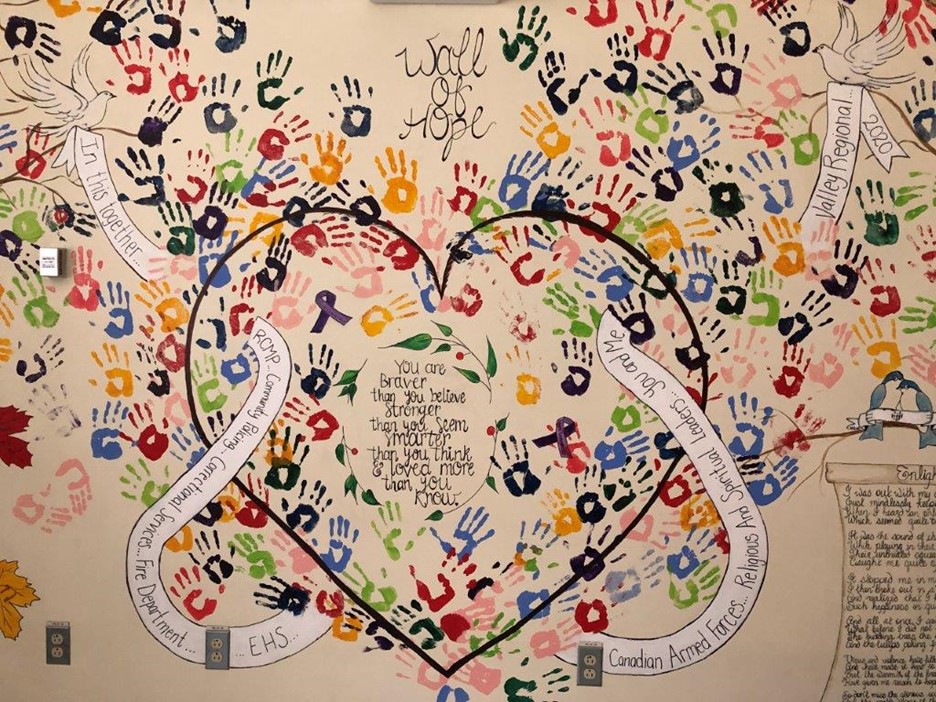

Wall of Hope

During COVID-19, Debra’s work, like a lot of people’s work, changed.

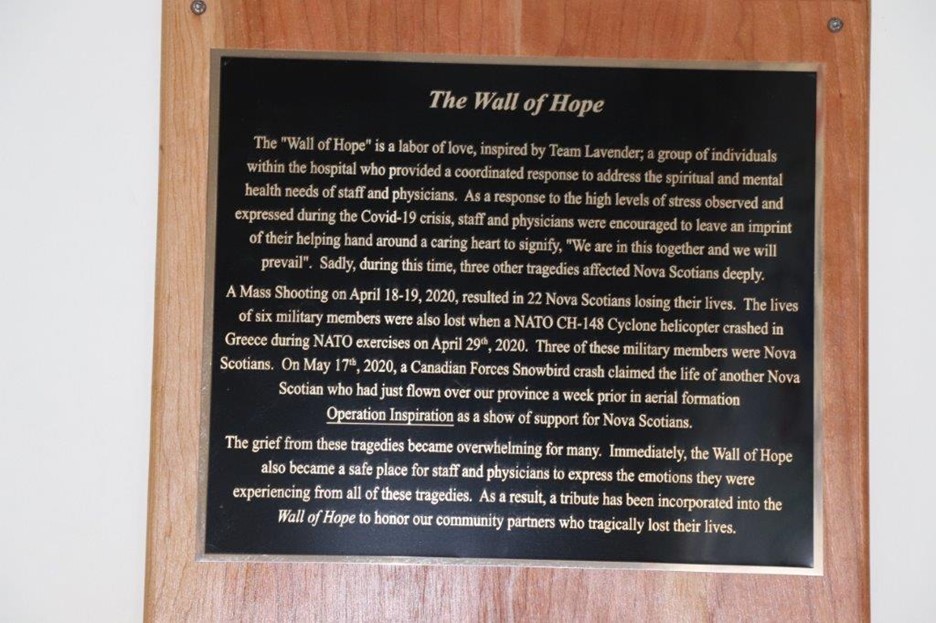

Yes, she works in healthcare during the biggest medical event in recent history. But in April 2020, just hours away from her workplace Canada’s worst mass murder happened. It claimed the lives of 22 people, and sent an entire region of the country into mourning.

Then, even more happened. The grief just kept piling on.

Later in April, three Nova Scotian military members died in a helicopter crash in Greece. One of them, Sub-Lt. Abbigail Cowbrough, just a week before her death, posted a video of herself playing Amazing Grace on bagpipes, honouring the victims of the Portapique, N.S. attacks.

In mid-May, a Canadian Armed Forces Snowbirds plane crashed, killing another beloved Nova Scotian: Capt. Jennifer Casey.

Essential workers, including those in healthcare, had to work through the whole thing. A job that was already stressful to the extreme, became unbearable to some.

“We’ve had some people come to us individually, saying ‘I think I need some extra help, I’m not sure if I can continue in my profession, I feel so stressed with everything that’s going on,’” says Debra. “Sometimes, we just don’t realize the stress is building up and it just takes one event to realize that our emotional valve finally needs to let go.”

The amount of formal debrief sessions Debra could do was limited during COVID-19, for safety reasons. But, she and her team found another way to help: the wall of hope.

The healthcare team in Debra’s hospital are multi-talented. Two registered nurses, Sharlene Van Roessel and Alex Marcia created the artwork for the wall of hope.

Poems, written by Dr. Lynne Harrigan and R.N. Julie Sutherland-Jotcham pay touching tribute to those affected, and offer loving words to hospital staff stopping by the wall.

Two emergency room doctors, Dr. Bruce McLeod and Dr. Lois Bowden took care of the thoughtful plaques shown below, designing and donating them to the hospital.

Debra says the wall of hope became a powerful tool for informal debriefing during the pandemic.

“It’s a place where they could gather, and place their hands, sometimes wherever they found their working partner’s hands were,” says Debra. “We’ve had different physicians and staff say that this wall of hope helped unite our hospital in a way it was never united before.”

What's Next?

While Team Lavender operated officially as a pilot project before COVID-19, Debra has big hopes and dreams for its future.

Debra has been tracking data this whole time. Her data shows that staff who visited Team Lavender after traumatic events were calmer, were more likely to seek out other resources if they needed them – and their teammates were actually calmer too.

In short: Debra proved Team Lavender has therapeutic value. She says after COVID-19, she plans to present her findings to Nova Scotia Health, and hopes she’ll be able to roll it out in more hospitals across the province.

Debra adds that she is willing to share her findings with any Health Authority in Canada.

When I asked Debra how she knows her work is done with each healthcare worker she talks to, she had the following to say:

“When I see them on the floor, back to themselves, being happy, and having their wonderful sense of humour,” Debra says with a bit of a laugh, but sincerely. “Because healthcare workers all seem to have a beautiful sense of humour – it gets us through the day sometimes.”

By Julian Abraham, Communications and Marketing Associate, HIROC